Playing Politics with Energy Security: How the Latest Congressional Budget Deal Raids the Strategic Petroleum Reserve

Looking to finally reach a longer-term agreement to avoid an extended federal government shutdown last week, a bipartisan deal was reached in Congress in the early morning of February 9 that would fund the government for the next two years. As the details of the deal get combed over there is plenty to digest, even in just energy-related topics (such as the inclusion of climate-related policy), but one notable part of the budget agreement was the mandate to sell 100 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The stated goal of this move was to help pay for tax cuts and budgetary items elsewhere in the deal, but will that goal be realized or is Congress paying lip service to the idea of fiscal responsibility at the expense of future energy security?

Purpose and typical operation of the SPR

In a previous post, I covered more extensively the background and purpose of the SPR. In short, the SPR is the largest reserve supply of crude oil in the world and is operated by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). The SPR was established in the wake of the oil crisis of the late 1970s with the goal of providing a strategic fail-safe for the country’s energy sector– ensuring that oil is reliably available in times of emergency, protecting against foreign threats to cut off trade, and minimizing the effect to the U.S. economy that drastic oil price fluctuations might cause.

In general, decisions regarding SPR withdrawals are made by the President when he or she 1) “has found drawdown and sale are required by a severe energy supply interruption or by obligations of the United States under the international energy program,” 2) determines that an emergency has significantly reduced the worldwide oil supply available and increased the market price of oil in such a way that would cause “major adverse impact on the national economy,” 3) sees the need to resolve internal U.S. disruptions without the need to declare “a severe energy supply interruption, or 4) sees it a suitable way to comply with international energy agreements. These drawdowns, following the intended purpose of the SPR, are limited to a maximum of 30 million barrels at a time.

Outside of these standard withdrawals, the Secretary of the DOE can also direct test sales of up to 5 million barrels, SPR oil can be sold out on a loan to companies attempting to respond to small supply disruptions, or Congress can enact laws to authorize SPR non-emergency sales intended to respond to small supply disruptions and/or raise funds for the government. This last type of sale is what Congress authorized with the passing of the budget deal (see the previous article on the SPR to read more about how the SPR oil actually gets sold).

Source: Oil Price

While selling SPR oil to raise funds is legislatively permitted, this announced sale of 100 million barrels (15% of the balance of the SPR) is an unprecedented amount– the biggest non-emergency sale in history according to ClearView Energy Partners. More concerning than the amount of oil to be sold, though, is the ambiguity behind what exactly the sale of SPR oil will fund. Historically, an unwritten and bipartisan rule was that the SPR was not to be used as a ‘piggy bank’ to fund political measures. However, that resistance to using the SPR as a convenient way to raise money (for causes like infrastructure or medical research) was waned as Congress has faced the perennial opposition to raising taxes and the need for new sources of income.

Lisa Murkowski, Chairwoman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, has echoed these frustrations about how the funds from the SPR sell-off will be used. When asked how Congress would spend the money, she simply replied it would be spent on “whatever they want. That’s why I get annoyed.” Despite the history of the SPR being an insurance policy for the U.S. energy sector and economy from threats of embargo from foreign nations, natural disasters, and unexpected and drastic changes in the market, the inclusion of SPR sales in this budget is just further indication of Congress trading out energy security and buying into other priorities. Taking the issue a step further, once the oil from the SPR is sold off, it likely becomes that much harder to convince Congress in the future to find the money to rebuild stocks with any additional oil stocks that might become necessary, both because the trajectory of oil prices is always climbing and thus naturally becomes more expensive to do so over time and because getting Congressional approval for new spending will always be more difficult politically than ‘doing nothing’ and just keeping SPR stocks at their current levels.

But is this selling of the SPR oil really in the name of deficit reduction and fiscal responsibility? Will the sale of this oil make an appreciable difference and help balance out the budget that Congress agreed to at (or, rather, past) the eleventh hour?

Crunching the numbers

Ignoring the previously authorized SPR sales, this budget deal alone included directive for DOE to sell 100 million barrels of oil from the SPR. What level of funds would this actually raise, and would it be enough to make a dent in the deficit? At current prices of crude oil that have hovered in the $60 per barrel (b) range, the sale would translate to about $6 billion– but the actual number depends on the price at which the oil gets sold, an uncertain number because the oil is being sold over the next 10 years and oil prices are notoriously variable.

We can make a certain degree of estimates based on the outlook of crude oil prices going forward (acknowledging at the outset the significant uncertainty that any forecast inherently assumes, especially in the oil markets that are affected by outside factors like government policy and geopolitical relations). To get a rough idea, though, we can look at the recently released 2018 Annual Energy Outlook (AEO2018) from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) which projects energy production, consumption, and prices under a variety of different scenarios (such as high vs. low investment in oil and gas technology, high vs. low oil prices, and high vs. low economic growth).

Brent crude oil (representative of oil on the European markets) starts at about $53/b in 2018 and goes up to about $89/b by 2027 in the ‘reference case’ (going from $27/b to $36/b in the low oil price scenario and $80/b to $174/b in the high oil price scenario). Similarly, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil (representative of the U.S. markets) starts at about $50/b in 2018 and goes to $85/b in 2027 in the ‘reference case’ ($243/b to $33/b in the low oil price scenario and $48/b to $168/b in the high oil price scenario). These figures present a pretty wide range of possibilities, but that is unfortunately the nature of oil prices in today’s climate. Further, EIA does unofficially consider these ranges to be akin to the 95% confidence intervals between which the actual prices are almost assured to be found, so we can still find value in these prices as the ‘best’ and ‘worst’ case scenarios.

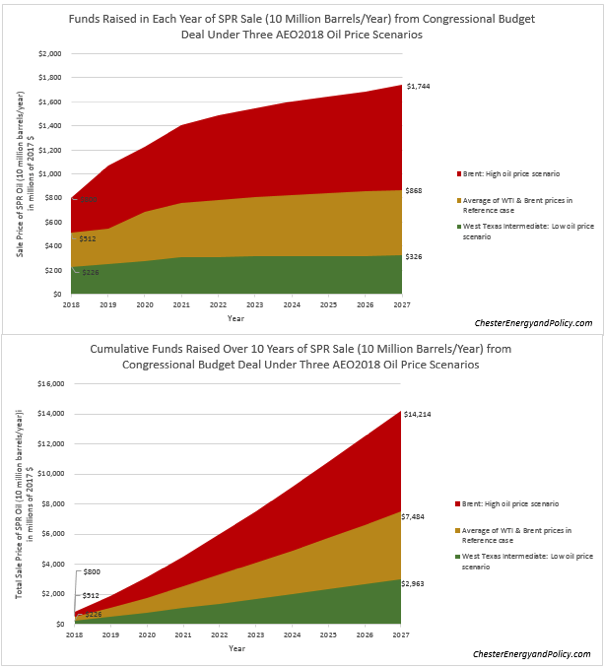

For simplicity’s sake, we can assume this 100 million barrels sold will be sold in equal chunks of 10 million barrels per year from 2018 to 2027 (though the actual sale will certainly not follow this neat order, but the assumption will get us in the approximate range). In the below charts, see the amount of funds raised from this SPR sale assuming the actual sale price is the average of Brent and WTI prices in the AEO2018 reference case compared with using the price of Brent in the high oil price scenario (the largest total oil price in any side case) and the price of WTI in the low oil price scenario (the lowest oil price in all of the side cases). The top chart tracks the amount of money raised in each of the 10 years while the bottom chart then shows the cumulative money raised in these three scenarios over the course of the decade.

As shown, the low oil price scenario raises between $226 million and $326 million every year for a decade, totaling just shy of $3 billion in funds. In the high price scenario, the annual amount brought in is between $800 million and $1.7 billion per year, totaling about $14 billion in funds. In the reference case, the one that is most likely (though not at all assured) to be representative, each year the selling of SPR oil would bring in between $512 million and $868 million for a total of $7.5 billion in funds.

Now let’s be clear about one thing–raising somewhere between $3 billion and $14 billion is a lot of money. But in the context of this budget that was passed and the rising deficit of the federal government, how much of a dent will this fundraising through the sale of SPR oil really make?

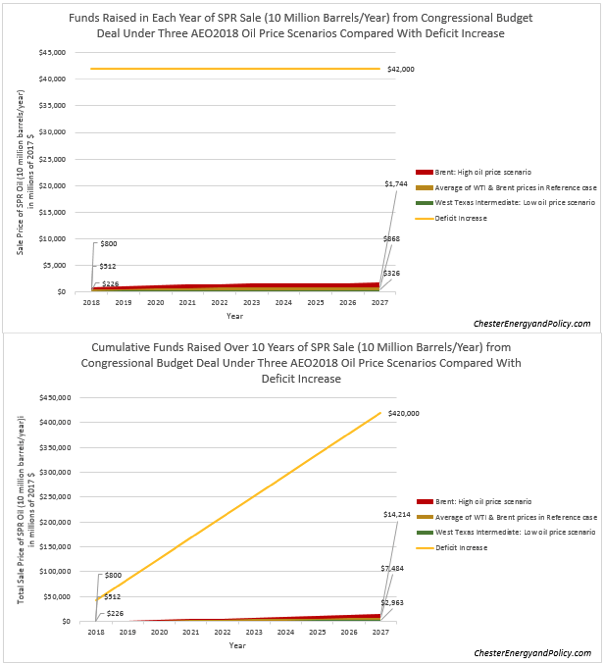

The budget deal will add $320 billion to deficits over the next decade, which is almost $420 billion when factoring in interest according to the Congressional Budget Office. That massive increase in spending, an average of $42 billion per year, makes the funds from the SPR sale look like pocket change:

Both the sale of SPR oil and the impact of this budget will be felt over the next 10 years, meaning these dollar figure present very apt comparisons. At the end of the decade, the high oil price scenario shows that SPR oil sales will only account for 3.4% of the deficit increase, while the reference case would account for 1.8% of the deficit increase and the low oil price scenario would only account for 0.7% of the deficit increase. Since the deficit would increase over the course of 10 years, another way to think of it is that the selling of SPR oil would account for 124 days of the deficit increase in the high oil price scenario, while the reference case would account for 65 days of the deficit increase and the low oil price scenario would account for 26 days of the deficit increase.

Outside of the increase to the deficit, the discretionary spending from the budget increase are to be $296 billion over the next two years (not including money given immediately to disaster spending, healthcare, and tax cuts). The SPR oil sale translates to between 1.0 and 4.8% of the discretionary spending increase or 7 to 35 days of the two years worth of spending increases.

Lastly, after accounting for this latest Congressional budget agreement, the CBO projects the federal deficit will increase to $1.2 trillion in 2019. If the sale of SPR oil is attempted to be pushed as a degree of fiscal responsibility in the wake of this budget deal, it is worth noting that the authorized sale of the SPR oil would only account for 1.2% of the total federal deficit in the best case scenario of high oil prices (0.2% in the low oil price scenario)– a metaphorical drop in the bucket (though for those curious, it’s actually significantly more than a literal drop in the bucket!).

What’s it all mean?

Buckets get filled drop by drop all the time, and it inherently requires many drops to fill up that bucket. So in this metaphor, each drop need not be disparaged for not being larger and doing more to fill up the bucket as it is the aggregate effect we should care about. Despite that truth, it is still fair to bring up whether the sacrifices required to gather that ‘drop’ were worthwhile. Going back to the origin and history of the SPR, Congress selling off large portions of the stocks of oil was never meant to fund ambiguous budgetary measures.

This 100 million barrels to be sold should also not be taken without the context of the sales already authorized by Congress last year that will also become reality in the next decade. Combined with the previously mandated sales, after this budget deal the SPR will be left with just over 300 million barrels of oil— about half of what it had been. So the negative side of this is that Congress appears ready and willing to gut the SPR. However the other side is that, because of the U.S. shale oil boom and other factors, the amount of net imports of oil and oil products to the United States has been dropping significantly. In the context of decreasing net imports, the amount of SPR stock measured in terms of ‘days of supply of total petroleum net imports’ has seen a comparable rise. What this means is that because the United States has become less dependent on foreign oil, less oil needs to be stored in the SPR to provide the same amount of import coverage.

In the wake of this budget passing and the previously announced SPR oil sales, many energy analysts came out to call these moves short-sighted at best, citing the following among the many reasons:

The recent hurricane season and resultant refinery outages showed just how valuable the emergency reserves are to the nation;

The risk of supply disruptions to the United States isn’t confined just to the level of oil available (which the nation’s lower levels of imports works to mitigate), but the risk also includes the price increases to the overall market that would occur regardless of import levels and disrupt the U.S. economy;

The SPR is a valuable foreign policy tool, offering the United States and its allies insulation from foreign threats to withhold oil supplies as a means of political ransom, so reducing the SPR stocks weakens that tool; and

All of this is not even to mention that an immediate side effect of selling such a large amount of SPR oil would be to reduce the price of oil and harm U.S. oil producers as a result.

Because the budget that was passed was over 600 pages and was voted on before most people (or anyone) would realistically have a chance to read it, it’s yet to be clear what part of the budget will cause the most noise. But in terms of this surprising move by Congress with respect to the SPR, the questions to wrestle with become the following: Is it wise to sell off our oil insurance policy that might be needed in future tough times just because things are looking good for the present U.S. oil market? Is the financial benefit of reducing SPR oil stocks by such a significant amount worth paying off a couple of weeks to a couple of months of the increased deficit, or is it possible that such a sale is only paying lip service to fiscal responsibility that allows politicians to point to an impressive sounding source of funds (up to $14 billion!) when in reality it doesn’t move the needle much (a maximum of 3% of the increase in deficit)?

If you enjoyed this post and you would like to get the newest posts from the Chester Energy and Policy blog delivered straight to your inbox, please consider subscribing today.

For some additional takes on energy policy decisions proposed by the Trump administration, please see other posts on the EPA administrator’s energy policy decisions, the push for ‘clean coal,’ the opening of the Alaskan National Wildlife Reserve to drilling, and rewriting the punchlines to some of the White House correspondents’ dinner jokes to take aim at energy and climate policy decisions.

Sources and additional reading

2018 Annual Energy Outlook: Energy Information Administration

America’s (not so) Strategic Petroleum Reserve: The Hill

Budget deal envisions largest stockpile sale in history: The Hill

CBO Finds Budget Deal Will Cost $320 Billion: Congressional Budget Office

DOE in Focus: Strategic Petroleum Reserve

Harvey, Irma show value of Strategic Petroleum Reserve, energy experts say: Chron

Petroleum reserve sell-off sparks pushback: E&E Daily

U.S. Looks To Sell 15% Of Strategic Petroleum Reserve: OilPrice.com

U.S. SPR Stocks as Days of Supply of Total Petroleum Net Imports: Energy Information Administration

Weekly U.S. Ending Stocks of Crude Oil in SPR: Energy Information Administration

Why the U.S. Shouldn’t Sell Off the Strategic Petroleum Reserve: Wall Street Journal