Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist and Other Essays

I was initially attracted to Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist and Other Essaysby Paul Kingsnorth by the title. Obviously, Kingsnorth is still someone who cares deeply for environmental and green issues, so his coy self-identification as a ‘recovering environmentalist’ and his frustration with the state of today’s ‘green’ movement intrigued me enough to pick his book up from my local bookstore. What I quickly realized was that Kingsnorth was not merely frustrated, but had rather completely denounced what the movement had become and was using these essays as a means of reflection on how the movement, and Kingsnorth himself, got to where they are today. He explains:

Over the years, I had felt fury, frustration, depression, anger, determination and many other, more mixed, emotions as I contemplated the wreck we were making of a bountiful and living world. For most of my twenties, I had put a lot of my energy into environmental activism, because I thought that activism could save, or at least change, the world. By 2008 I had stopped believing this. Now I felt that resistance was futile, at least on the grand, global scale on which I’d always assumed it had to occur. I knew what was already up in the atmosphere and in the oceans, working its way through the mysterious connections of the living Earth, beginning to change everything. I saw the momentum of the human machine– all its cogs and wheels, its production and consumption, the way it turned nature into money and called the process growth– was not going to be turned around.

Essentially, as he fought for what he thought was important in nature, he saw little to no progress while a new concept of ‘sustainability’ co-opted the green ideals, taking them in a direction in which he did not agree. As someone embedded in the energy industry specifically, I read through Kingsnorth’s writings to try and understand his perspective, a self-described eco-centric who cares predominantly about allowing the Earth to persevere at its natural state while characterizing humanity’s excesses as truly secondary. While I was able to gather some nuggets of insight and wisdom that I find will be important for me to keep in mind moving forward, more than anything I found myself rejecting the attacks on today’s green energy movements. While Kingsnorth would have us return to more ancient times before technology progressed if it meant preserving the natural world, I would accuse him of letting the ideal of perfect be the enemy of the good. Just because we don’t have a silver bullet picked out that allows human progress to continue in a way that preserves the natural world around us perfectly does not mean those with such ideals should just give up and retreat to the woods (as Kingsnorth romanticizes)– we should harness our collective ingenuity to find a middle ground that preserves and restores natural spaces while allowing all the profound good done by human progress (fighting hunger, disease, and more) to continue.

Connections to the energy industry

As previously noted, I read this book from the perspective of someone inside the world of energy who also agrees with the broad notion that our development of energy resources should be done in a way to minimize or completely eliminate negative impacts to the environment. While most of this book does not directly address energy (rather it gets more into the philosophy of man vs. nature and how that relationship has evolved over the millennia), I did want to provide an overview of the parts of the book that were relevant to readers like myself who are most focused on energy topics.

Kingsnorth clearly expresses his detest for today’s renewable energy push, mostly backed by the idea that solar, wind, and hydroelectric power are promoted by people who would suggest they are harmonious with nature (due to their carbon-neutral fuel sources and relative lack of waste product) when he instead finds that all they do is enable and propagate the ills of human over-consumption and overtake land that could otherwise be left as wilderness. For example, with regard to hydropower (the most significant source of renewable energy in the United States today) Kingsnorth writes:

Today, mega-dams are as popular as ever, and are often dressed up as yet another ‘renewable solution’ to the climate change caused by the development of the model they were originally a part of. It’s the same old mutton, now dressed up as low-carbon lamb, and we are still hooked on it. It gives us– some of us– power, order, control, national pride. It allows us to grow, for a while. We can drown the past, and much of the inconvenient present, under hundreds of feet of water and hope it never rises again to show us what’s beneath this surface.

This attempt to paint hydropower negatively because it continues to enable dependence on such control over nature in order to power our technology is short-sighted. The main crux of Kingsnorth’s argument is that humanity continues to look for renewable energy sources that will meet our energy needs while minimizing or eliminating greenhouse gas emissions, but our determination about the energy we need is horribly misguided. Talking about these energy needs, he asks:

But our needs for what? Coffee machines and fast broadband, or clean drinking water and living ecosystems? Middle-class life in a consumer democracy or a livable human existence? Or do we think these are the same thing?

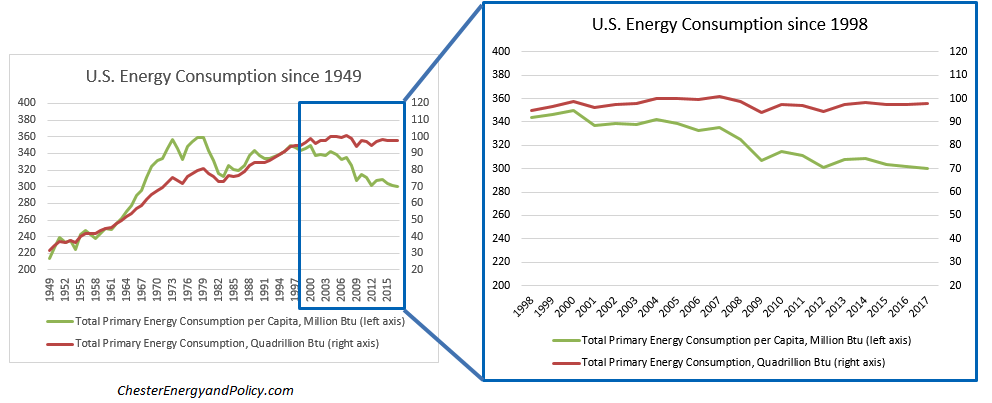

In presenting the false choice between the two extremes, I can’t help but think of a teenager who just watched Fight Club for the first time who now wants to rail against the faceless corporations and overt consumerism. While there are certainly seeds of truth in the idea that humanity is a glutton for excess, one does not need to tear the system down to the ground and start over in order to fight that trend. Not only are you dismissing all the immense good that has been brought to the world by our ability to provide energy, but there’s also a middle ground that involves embracing energy efficiency, sustainable design, and localized energy generation. In fact, the energy use in the United States has actually flattened in the past 20 years and experienced a per capita decrease of 13% despite our growing reliance on powering technology– trends that should give some hope that there is progress to be made in reducing our perceived energy needs through continued progress.

Despite the passion that is clear in his writing, Kingsnorth seems to have little faith in humanity, asking “What is to be done about this? Probably nothing. It was perhaps inevitable that a utilitarian society would generate a utilitarian environmentalism.” He blames today’s push for sustainability, something he calls a “curious, plastic world,” for giving humans an excuse not to defend the natural world from the ever-expanding touch of humans and their needs. Going further, Kingsnorth is fearful that accomplishing sustainability “will require the large-scale harvesting of the planet’s ambient energy…which means the vast new conglomerations of human industry are going to appear in places where this energy is the most abundant, coinciding with some of the world’s wildest, most beautiful and untouched landscapes.” In this vision, he sees a future that looks to him like a horror movie, solar and wind energy generation taking over deserts, mountains, and oceans, all resulting in “mass destruction of the world’s remaining wild places in order to feed the human economy.” I would say that Kingsnorth brings forth a fair point regarding how new renewable sources are integrated into the natural world, and such considerations should certainly be factored into future energy policy. But I also don’t think it is fair to use that fear as a reason to completely dismiss renewable resources and other possible innovations human will certainly find.

The rest of the good

Before further arguing against some of Kingsnorth’s main points, I do want to point out some of the points that resonated with me. First and foremost, the reverence Kingsnorth has for nature jumps through the pages. Regardless of whether or not I agree with the exact conclusions to which that passion leads, much of this book could be considered a love letter to nature that was truly contagious. Kingsnorth uses this passion to create an emotional plea for nature being protected, rather than a purely data or science-based argument. All things natural, he writes, “are food for the human soul and they need people to speak for them to, and defend them from, other people, because they cannot speak our language and we have long forgotten how to speak theirs.” This appeal to emotion, how nature and wild space make us feel, is very powerful. He rejects the economic analysis of our use of land, as doing so only creates crutches and by relying on them we then set a precedent that if the data does not hold then the land is inherently not important (another excellent read on the dangers of a society that has learned to only respond to data is The Tyranny of Metrics). While I personally rely heavily on data and statistics, I can appreciate Kingsnorth speaking to this non-quantifiable, more emotional side. I agree with the notion that we need to preserve nature for the sake of preserving nature, not just if economic analysis dictates. More than anything, the importance of including emotion and spiritual connection to nature in any discussion of development of natural resources is my biggest personal takeaway from this book.

Another successful point Kingsnorth made that applies to energy development is that the vast and readily-accessible information the Internet provides us today does not always result in more informed citizens. As one example, he writes:

The fight between pro-nukers and anti-nukers [for and against nuclear energy, not nuclear weapons] is actually quite archetypal. Though both sides pretend to be informed by ‘science’ and ‘facts’ both are actually primarily by intuition and prejudice. Whether you like nuclear power or not is a reflection of the kind of worldview you have: whether you are a confident embracer of the Western model of progress or whether it frightens or concerns you, whether you trust science or tend not to; whether you are cautious or reckless; whether you are ‘progressive’ or ‘conservative.’ On issues from GMO crops to capitalism, these are the underlying stories that inform the green debate. That they are then supported by a clutch of cherry-picked facts– easy to come by after all in the age of Wikipedia– is a footnote of what’s really going on.

As anyone who spends time debating energy topics (whether on Twitter, letters to the editor, or in public forums) can attest, many people who hold passionate opinions end up finding what they want to find from the deluge of information and arguing with it ardently. An important lesson for anyone in these debates is to both recognize this tendency in themself so he or she can strive for objectivity, while also identifying it in the people on the other side to better understand their perspective.

Qualms

I did, however, take issue with many of the points Kingsnorth expressed regarding humanity and our relationship with the Earth. My most significant qualm was with the dismissive attitude of human progress. Kingsnorth focuses on the excesses to which humanity has become accustomed and how those comforts contribute to the degradation of the Earth. While I understand his preferred life might be one where he exists in the remote wilderness separated from civilization, he’s also using modern tools to write, research, and communicate his ideas. In doing so, he exemplifies how it’s not actually a realistic exercise to separate yourself from the human machine. He admits as much when discussing how his goal to plant a sustainable forest on his land resulted in relying on the ability to drive to get the new trees, the information he read as research, and more. But then he also discusses his efforts to install a compost toilet (essentially a bucket and some sawdust) in replacement of plumbing for his family. While I can understand his spiritual quest to return to nature and simplicity, by dismissing human progress he’s not recognizing the amount of disease staved off by modern plumbing, the advanced medical technologies we’ve created thanks to an electric grid, the hunger eradicated by the modern food industry, etc. While I agree there are kernels of truth to the idea we should approach Earth as a member of its community and not the gods of it, I think he takes this characterization too far. Sounding eerily like certain characters (no spoilers!) in The Three-Body Problem who determine humanity might not even be worth saving, Kingsnorth writes:

Anything could happen in the next hundred years. The two extremes? Well, we could devastate the Earth and collapse into chaos and runaway climate change. Or we could create a global ‘sustainable’ society based on large-scale renewable tech, massive rollout of GM crops, nanotechnology and geoengineering– a controlled world of controlled people living in a closely monitored scientific monoculture. Brave New World with wind farms and smartphones. Which would be better? Who would deliberately aim for either?

In a practical sense, that’s not a notion I can get behind. Perhaps I’m naive, but the idea that we have evolved such intelligence (and the technology to maximize the use of this intelligence) but should not use it to prolong and enhance the existence of humanity seems absurd. While societies have never reached a consensus on the ‘why are we here?’ or ‘what is the purpose of life?’ questions, I find it hard to accept any argument that does not agree that humans should work to stave off their own extinction. In doing so, we 100% should also apply that same effort to protecting the rest of nature– and despite Kingsnorth’s disdain for human beings, is it not telling that the polar bear has long been the emotional symbol behind fighting climate change rather than any human creation?

In furthering his argument that humans are overly self-focused, Kingsnorth even brings up the previous mass extinction events in the billions of years of Earth’s history, events that created a world hospitable for humanity today, to show that large-scale environmental changes like climate change are perhaps the natural state of things. He writes that “the nature of this Earth is endings. The nature of this Earth is extinction…Earth is an extinction machine, and it has been here before…the ecological crisis we hear so much about, and that I have written so much about and worked to stave off– well who says it’s a crisis?” Kingsnorth seems resigned that climate change is just going to happen to us and, since we are unwilling to reverse the wheels of progress backwards and just live off the land, there’s nothing we can do and we should accept this changing Earth that will eventually reject its human infection. While he acknowledges and even fears how close some of his reflections mirror those of the Unabomber’s loss of faith in humanity before detailing how his philosophies are ultimately different, I cannot be swayed away from the optimistic part of humanity who sees the various problems we have and wants to innovate to solve them, whether that means colonizing Mars as Elon Musk suggests or living aboard a spaceship looking for a hospitable home like in Wall-E. Humans always have and always will be agents of progress and change, so in lieu of fighting that change or giving up completely, I think it makes more sense to continue to work to ensure that progress is made in a way that does the best for humanity while minimizing our impacts on the Earth.

Rating

Content- 2.5/5: Kingsnorth clearly knows his stuff and is passionate about his evolving environmental views, but with his conclusions being fraught with hypocritical views and an attitude that humanity is already lost, I can’t give the content of this book more than half credit.

Readability- 4/5: Kingsnorth is a writer through and through, and while I may not agree with many of his opinions, he is able to express them to the reader with clarity and vigor. The book is broken down into different essays written over the years, so it’s also easy to read in digestible chunks.

Authority- 2/5: Even with my frustrations on how he treats humanity as a lost cause, my biggest issue is with how wrong he gets renewable energy technologies. These advancements are able to pull third world nations out of poverty, save many lives, and hopefully prolong the existence of humanity on Earth. If those aren’t causes worth fighting for, I don’t know what else to say.

FINAL RATING- 2.8/5: I can understand the frustrations driving this book, but I think the conclusions are short-sighted and naive. Kingsnorth has left his environmental activist roots to pivot more towards philosophical than pragmatic (not necessarily a bad thing) and dismissive rather than constructive (I do think that’s a bad thing). All in all, it is an interesting read that provided me with a new perspective and some nuggets of wisdom that I’ll keep, but an overarching philosophy I can’t fully advocate.

If you’re interested in following what else I’m reading, even outside of energy-related topics, feel free to follow me on Goodreads and see my page of energy-related book recommendations. Should this review compel you to pick up Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist and Other Essays by Paul Kingsnorth, please consider buying on Amazon through the links on this page.