Split Incentives in the World of Energy: What Power Use in Rental Properties Can Teach Us About the Larger Politics of Renewable Energy and Climate Change

While recently travelling, I was cozy and tucked in bed under full sheets and comforter with the thermostat set to 65 degrees, when I felt a pang of guilt about this unnecessary energy usage. I grumpily got out of bed to adjust the temperature when it hit me. As an advocate for energy-efficiency and climate-change efforts, I never would have set the thermostat so low if I was at home, so why did I act differently while in a hotel room?

The obvious difference relates to who’s paying the power bill. The experience led me to wonder about the disconnect when the costs and benefits of reducing energy usage falls to different parties, a concept known as split incentives. Further, these instances of split incentives on an individual scale led to questions of how split incentives and their solutions could apply to energy and climate issues on the larger scale.

Examples of individual-scale split incentives

Hotel energy use

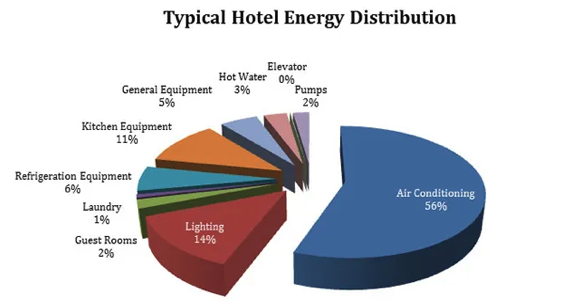

The issue: Hotels have the long-established expectation that guests will not be required to pay for their energy use. This setup is ingrained in the culture of hotels, and as such, most people can relate to the feeling of checking into a hotel after a long day of travel and cranking up the thermostat more freely than they might have at home, leaving the lights on out of laziness, or permitting themselves a luxurious extra-long hot shower. Considering those mini-vacations from energy concerns, the fact that hotels use 36% more energy per square foot than residential properties is unsurprising. While many factors obviously feed into that difference, the disconnect between using and paying for power is certainly one at play.

Source: Energy Dynamics

The solutions: Hotels don’t install energy meters in each room, and the cost to do so would be immense. More fundamentally, though, who would want to stay at a hotel that nickel and dimes you for using the air conditioner on a summer day? Given these constraints, a few more feasible solutions are available:

Some hotels already use energy saver keycard switches that require a guest’s hotel keycard to be inserted in order to power the room’s lighting, heating and cooling, and other power usages, preventing the wasting of energy when the room is unoccupied.

While no hotel would be mad enough to increase rates for guests who use too much energy, energy-conscious hotels could offer rebates or future discounts for guests who took energy-saving actions such as forgoing new towels each day, keeping the thermostat within a predesignated temperature range, or limiting time with the shower running (some green hotels already install five-minute hourglasses in the showers to nudge guests to take shorter showers).

Rental properties

The issue: The more traditional example of split incentives is with long-term rental properties. When a tenant is paying the power bill, the building owner has minimal incentive to install energy-efficiency measures (e.g., insulation, more efficient appliances, or even rooftop solar) because they would not receive cost savings to pay back their capital investment. On the other hand, when tenants are charged a flat fee that includes all utilities, regardless of how much power was used (affording tenants predictability in monthly bills, while preventing landlords the need to install energy monitors in each unit), the tenant has no financial incentive to conserve energy, resulting again in more liberal use of the thermostat and leaving appliances on when not in use (not to mention how this arrangement also leads to higher rent prices as landlords increase rates to pay for ballooning power bills).

Source: Energy Center

The solutions: Rental-property split incentives have been tackled through many types of solutions, including the following:

For buildings without them, installing energy meters in each individual unit is a first step. Landlords that only have a single reading from a building have limited options, all of which suffer from split-incentive downsides. Unfortunately, energy monitors are costly to install and thus might be ignored as an option by landlords who do not recognize that long-term savings that would be enabled.

Green leases are a potential solution, allowing for the costs and benefits of energy-efficient improvements to be split between owners and tenants. For example, say a landlord wants to install energy-efficient windows, which are expected to save $50/month on energy bills. If the utilities are paid by the tenant, a green lease could allow the landlord to increase rent by $40/month to recoup investment costs, but the tenant still realizes a $10/month net savings. Similar mechanisms to allow tenants to receive the benefits of energy upgrades include on-bill financing programs or community-funded solar installations.

A radical proposal to make both tenant and landlord invested in saving energy is having utilities work more like cell phone plans. In this setup, the landlord would allow for a certain limit on energy use each month, similar to the limit on phone call minutes allowed through a cell phone plan, and if the tenant exceeds that limit then the landlord collects ‘overage charges.’ In this way, landlords would pay the power bills of most tenants and be personally motivated to install energy-saving measures, but tenants would remain mindful to not use unnecessarily excessive energy.

While politicians tend to shy away from sweeping regulations, lighting standards that pushed Americans from incandescent light bulbs to CFLs and LEDs are an example of a successful implementation of government-mandated efficiency requirements that now save everyone energy and money. Specific to split incentives, the nation’s first energy code specific to rental properties was implemented in Boulder, Colorado, successfully saving tenants an average of $361/year while reducing greenhouse gas emissions by almost 30% from those properties.

Global energy and climate accounting issues

Unfortunately, renewable energy penetration and CO2 emission reductions largely only matter to countries, states, and organizations when they can be counted and credited, comparable to how individual energy use only ends up mattering to those paying the energy bill. Such tendencies are the natural consequence of a world that is increasingly over-concerned solely with progress that can be measured by metrics (for more on this topic, I highly recommend the book The Tyranny of Metrics).

Shipping emissions across borders

The issue: A common criticism of policies addressing greenhouse gas emissions from U.S. industry is that such actions simply result in the affected companies moving their operations overseas to avoid regulation. In these instances, global emissions remain constant– perhaps even worse because those products now must be transported back stateside. Regardless, the accounting of emissions for U.S. industry appears improved and the policy deemed effective because the CO2 associated with those products are shifted into another country’s emissions log. This trend also applies to the transport of electricity across borders. For example, keen-eyed observers note that both California and British Columbiameet their emissions targets by ensuring a higher proportion of the electricity productionwithin their borders comes from renewable sources, while simultaneously importing coal-based electricity through the grid and accounting for more emissions in their electricity consumption. But because this coal-based power is not in their production numbers, they can say they meet their targets. Worth noting, however, is that this type of disconnect can work in the reverse as well, such as the Northeast United States getting renewably-powered electricity from Canada.

Source: Master Builder

The solutions: The issue here is localized emissions regulations only address a piece of the puzzle, but global cooperation is the critical solution. Among the main impediments to such actions are the implementation costs. But if countries were able to see global climate cooperation as something for which they’d be rewarded rather than a cost, perhaps more progress would be made. Similar to how hotel guests would reject any hotel charging for power but would love rebates for energy savings, international climate agreements might have more luck in practice if they included financial rewards to nations for reducing emissions. Of course that money would have to come from somewhere, but the general idea is that leaders would be more easily able to agree to cooperation that showcases potential gains rather than losses.

Companies making hollow energy and climate commitments

The issue: Many corporations have begun taking responsibility to set emissions reduction targets and/or sourcing their power from renewable energy. Google and Apple both boast that they power their global operations with 100% renewable energy. However in each of these instances, the claims that all electricity fueling either tech giant is sourced from renewables is inaccurate and disingenuous. While these companies are funding solar and wind projects equal in amount to their power usage, such renewable energy sources are variable and the companies’ energy demands are not. As such, the energy used by Google and Apple at certain times comes from dispatchable (and non-renewable) sources like coal and gas, and power generated from renewable sources gets curtailed and wasted. The reality of these commitments is more of a practice in accounting than actual power delivery.

Source: Highfield PS

In the end, these companies may be delivering PR moves with more bark than Earth-saving bite. Further, some argue that these actions are even hollower for the climate than they seem, as they simply take credit for clean energy that was being created with or without the assistance of those corporations.

The solutions: An applicable lesson for more transparently controlling corporate emissions might come from the ‘cell phone plan approach’ to rental properties. Companies could be given a certain monthly allotment of emissions, as all organizations require due to the need to keep operations running when renewable sources are unavailable (e.g., days with too little sun for solar panels or too little wind for turbines). If they exceed that allowance, they can be charged for those excesses (not so different from a cap-and-trade approach). Such a plan would provide incentive for companies to embrace energy efficiency and a shift towards cleaner fuels, but would minimize the push towards somewhat illegitimate claims of being 100% powered by renewables.

Counting emissions

The issue: A recently published report made waves by calling into question the commonly accepted emissions associated with natural gas, an energy source heralded as cleaner than coal and a potential bridge fuel of the energy transition, stating that natural gas emissions were being severely undercounted in some instances. This study underscores how if underlying assumptions in accounting for emissions is off then the actions being taken might not actually make their intended difference in the climate change fight, but rather create perverse incentives to control for the faulty statistic rather than reality.

Beyond that, debate even persists regarding what constitutes renewable and/or carbon-neutral energy sources. Biomass fuel is technically renewable in that it comes from trees that can be replanted, but environmentalists and the biomass industry have been engaged in a tug of war about whether it should count as a renewable energy. Ethanol is a fuel that emits CO2, but because it comes from corn and sugarcane it is considered carbon-neutral. Even hydropower, the world’s oldest and most prominent renewable energy, has been shown to contribute a significant amount of methane from associated standing water.

The solutions: Accepted statistics for emissions from some energy sources do not necessarily line up with reality. Again, though, reality is what’s actually affecting the climate, whether or not we know exactly how to account for emissions.

The only real solution for this issue is to invest in the science and technology to get as close to the truth as possible. While installing individual power meters in hotel rooms or apartments is perhaps financially cumbersome, doing so is the only way to accurately assess the situation. Similarly, the only real way to properly address the emissions coming from the energy sector is to ensure that we have the right data. Those emissions are happening and affecting the climate regardless, so the beginning to any solution is being able to properly assess the problem. Otherwise, the reality will never reflect the potential emissions savings that are possible.

Conclusion

What’s most important to realize is CO2 emissions and climate change are global, not local, problems– so whether or not you are paying for the energy bill and whether or not the emissions count towards your country’s or organizations accounting sheet, the end result is the same. Numbers are useful as a benchmark, but these metrics we marry ourselves to should not be considered gospel– the only true way to know we are making progress: reduce energy use, minimize personal carbon footprints (both for individuals and organizations), and switch to less carbon-intensive energy technologies.

Are there other solutions to small-scale split incentives that can be applied to the world’s larger emissions and renewable energy accounting shortcomings? Let me know in the comments below or on Twitter.