Energy: A Human History

Early this summer, I excitedly discovered Richard Rhodes’ newest book Energy: A Human History. Rhodes previously won a Pulitzer Prize for his writing on the history of the atomic bomb, but in his latest book he turns to the history of how society discovered and interacted with various energy sources throughout time. While this book is no light beach read, I found that Rhodes’ approach and perspective made it unique compared with other treatises on the history of energy.

Source: Amazon

General notes and impressions

[This book’s] serious purpose is to explore the history of energy; to cast light on the choices we’re confronting today because of global climate change. People in the energy business think we take energy for granted. They say we care about it only at the pump or the outlet in the wall. That may have been true once. It certainly isn’t true today. Climate change is a major political issue. Most of us are aware of it– increasingly so– and worried about it. Businesses are challenged by it. It looms over civilization with much the same gloom and doomsday menace as fear of nuclear annihilation in the long years of the Cold War.

Rhodes is a historian by trade, but he avoids just taking the reader through a dry timeline of energy development. Rather, he hones in on key and compelling stories along that timeline, stories with which we’re likely unfamiliar, to highlight the notable characters and the captivating societal trends, and in that way he really makes the human part of energy come to life. Rhodes explains the importance of this telling of energy’s history, not just for the energy enthusiast but also for the common citizen who recognizes the world is at a pivot point:

Many feel excluded from the discussion, however. The literature of climate change is mostly technical; the debate, esoteric. It’s focused on present conditions, with little reference to the human past– to centuries of hard-won human experience. Yet today’s challenges are the legacies of historic transition.

With that, Rhodes invites everyone into the discussion to understand the how and why we got to the present day energy industry– all it’s great wonders and unfortunate ills.

Source: Penn State

Historical lessons

When I was early into this book, I read a colleague’s review that expressed frustration that Rhodes appeared to overlook the energy transition we’re currently experiencing. I was a little disappointed to hear this, but Rhodes himself notes “you will not find many prescriptions in this book—what you will find are examples, told as fully as I am able to tell them. Here is how human beings, again and again, confronted the deeply human problem of how to draw life from raw materials of the world.” After I read this passage and got a few chapters deep, I realized that Rhodes cleverly addressed the future in a different way. Through Rhodes’ treatment of historical stories on energy, the fact that these histories repeat themselves is undeniable. Rhodes was not shy about (and perhaps even took glee in) leaving this trail of breadcrumbs from the past to the present for his readers. As they say, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

This book tells the story of energy technologies in societies past, but in doing so it also tells the story of now and of the future. As proof, the following seven axioms represent a portion of those connections I made while reading Energy: A Human History.

1. Global energy addiction always comes with consequences

When society first became addicted to energy and its associated productivity increases (through coal and steam power), Rhodes traces how that energy production became so important it even sucked children into harsh factory and mining working conditions. A young girl testified in 1841: “I get to a pit at five o’clock in the morning and come out at five in the evening; I get my breakfast of porridge and milk first; I take my dinner with me, a cake, and eat it as I go; I do not stop or rest any time for any purpose; I get nothing else until I get home, and then have potatoes and meat, not every day…”

The parallel to today is how the exorbitant uses of energy are expected to be fed at all costs, but instead of sacrificing the well-being of children today in factories and coal mines we instead see the environmental ills of energy production harming children and we’re knowingly harming future generations who must deal with the consequences of climate change.

Source: The Guardian

2. Getting responsible parties in the energy industry to accept accountability for their negative externalities has always been difficult

Many energy production methods have inherent negative effects– be they pollution, climate change, impacts to national security, or otherwise– which need to be seriously addressed. While the efforts to have large fossil fuel companies accept responsibility for their negative externalities is often a hot topic in energy policy today (such as carbon taxes or fines for oil spills), I found it eye-opening to read that similar issues have always surrounded the energy industry.

The first instance of such efforts came from the coal industry. While the connection between coal-related air pollution and health problems was assumed by experts as far back as the 18th century, Rhodes contends that the true consequences weren’t really discovered in the United States until 1948 when mills belonging to U.S. Steel created a “death cloud” that hung over the city and was credited with hundreds of deaths in the Pittsburgh area. Half a century later, respected steel industry consultant Philip Sadtler told journalists “It was murder. The directors of U.S. Steel should have gone to jail for killing people.” At the time, though, the heads of U.S. Steel were reticent to admit fault. They ordered the mills shut down temporarily but assured the mayor they had nothing to do with the deaths. Not only was the power of U.S. Steel enough to dodge accountability, but Sadtler was even labeled a pariah by the industry after his comments went public. The steel industry refused to accept responsibility, even 50 years later.

Source: Wired

Rhodes discussed a similar blame-dodging incident where DuPont chemicals were being accused of harming local crops. In this instance, DuPont took steps to remove the chemical in question but refused to acknowledge connection between the harmed vegetation and their environmental practices– “In plain English,” Rhodes translates, “we don’t admit to doing it, but we’re cleaning it up.”

Energy companies have always sought to get what they need at all costs, and (if required) make amends later. I found this to be one of the more dispiriting “past meets the future” lessons from Energy: A Human History, because none of these past incidents really shined a light on future preventative solutions. Rather, all we can do is be hyperaware watchdogs of the present-day energy industry and their negative externalities (climate change, pollution, or otherwise), as history has shown a saddening tendency to only take ownership once they’re caught (and sometimes not even then).

3. Progress in newer energy technologies naturally comes at the cost of the older industries

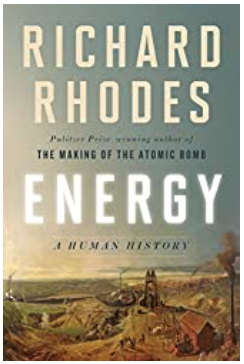

While energy innovation often inspires, new developments also bring fear to those whose livelihoods will be negatively affected. In recent times, for example, the U.S. coal industry has been losing market share thanks to challenges from renewable energy and natural gas, as well as political and international efforts to minimize CO2 emissions. In the face of such an onslaught, workers in so-called ‘coal country’ have fought back and maintained significant political clout– even finding a trusted ally in the Oval Office.

The fear from the coal sector is understandable (which is why focusing on new green job creation in these regions is critical), but a common dismissal you might hear opponents of coal is that the government didn’t bail out horse-and-buggy drivers when the Model T came along so why should this time be different? In fact, Rhodes masterfully paints the scene of how this statement isn’t just a catchy refrain, but the advent of the car did indeed disrupt the livelihood of many. Not just the drivers of horse carriages, but suddenly the demand for hay was greatly displayed. Many people lost their jobs in this transition, with Rhodes noting that “rural populations no longer required to grow [horses’] feed fell into permanent decline,” while those most threatened “recognized the danger of the new technology to their employment. They pelted the engine with cabbage stalks and rotten eggs.”

Despite the fears, these displaced markets were offered no subsidies or bailouts. Rather, the new technologies were eventually embraced and lifted these communities up as well. It’s a tale as old as time: as technology moves forward, those working with the displaced technologies will hit a roadblock, but those hurdles have always been overcome. Industries who might be negatively impacted in the short term by the clean energy transition are best served to get on board early, diversify their interests, and embrace the innovation– for example, oil giants Exxon, Shell, and BP have shown such awareness.

4. Economics, not good intentions or technology alone, are what drive innovation

Time and again through history, Rhodes shows that progress in energy only moves forward when it made business sense to do so, and good intentions alone are rarely sufficient to prompt change. For example, the steam engine was only invented and made workable when it was demonstrated the technology could make coal mines more profitable, not because of its ability to liberate people from perilous mining jobs, while the harnessing of electricity was only used as a parlor trick until astute entrepreneurs realized they could profit from it. Today, this need for the dollars and cents to come before anything else is reflected in renewable energy technologies, electric vehicles, and on-grid energy storage. The relevant and game-changing technologies have been available for years, but benefiting society has not been enough to move the needle. They’ve finally begun making headway as costs go down, potential money to be made goes up, and it doesn’t make business sense not to embrace them.

5. Even when the economics are there, politics can still impede energy progress

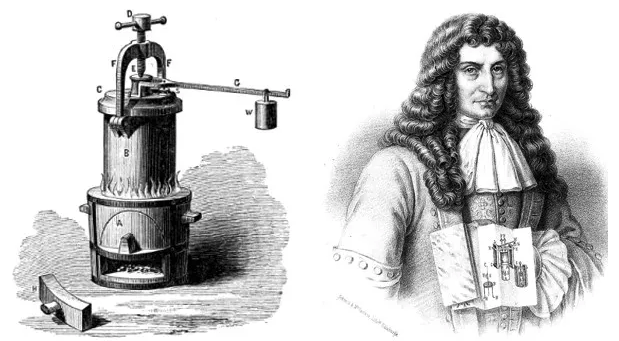

Rhodes gives fascinating treatment to Denis Papin’s journey after inventing the steam digester, the precursor to the steam engine, which was more affected with ugly politics than it was celebrated for his achievement. Papin was aligned with one of Isaac Newton’s foremost rivals in an unrelated matter– but this alignment meant that Newton’s Royal Society refused to fund and support Papin’s work, despite its obvious scientific importance. This high-profile grudge getting in the way of science and progress undoubtedly parallels issues in the energy industry today, debates including carbon taxes, bailouts of coal plants, and the political peril that prevents the embrace of nuclear power.

Source: Asynt

6. Society needs to be ready for new technologies in order for them to take hold

A common theme sewn throughout the energy stories Rhodes weaved was the idea that technology can be completely operational and commercially ready, but society might ignore that technology if the timing isn’t right. Rhodes notes that “nearly all important discoveries pass through a stage of neglect and obscurity…Either the public attention is already preoccupied, or the discoveries come at a time when the public are not prepared for them and they are disregarded.”

The advent of the automobile was a chief example of this concept. Rhodes relays the worlds of Hiram Percy Maxim, an automobile pioneer, who said “It has always been my conviction that we all began to work on a gasoline-engine-propelled road vehicle at about the same time because it had become apparent that civilization was ready for the mechanical vehicle.” The raw technology necessary for the internal combustion engine had been available, but Maxim realized no one had really dove in previously because society had not pushed for or been ready for such an innovation. But once the world was in a place where the automobile could readily take hold, inventors got to work.

Source: Courant

This theme applies to many energy technologies on the cusp of breakthroughs today, such as large-scale energy storage, systems of localized microgrids, or hydrogen cells. Most relevant, in my opinion, is the electric vehicle. While the industry continues to improve their performance and cost, electric cars have been technologically and commercially available for years, and yet they have not yet reached an inflection point of adoption. But today’s environment of energy and climate awareness presents a society that might finally be ready to accept widespread adoption of electric vehicles.

7. Energy transitions are rarely complete

Rhodes guides the reader through some of the most significant energy transitions of the past few centuries, but in doing so he highlights how energy transformations are rarely (if ever) actually complete. Even when the steam engine was becoming increasingly prevalent, the number of horses being used for work actually increased because the power of horses filled the niche needs just below steam power– niche needs that were in more demand than ever due to the explosion in productivity that steam engines created. While many would have thought steam engines would eliminate the horse as a means of production, it actually accomplished the opposite. Several times in the book, Rhodes reminds the reader that energy transitions are seldom so complete that they drive out every competitor. In that way, energy experts of today should remember that ‘100% renewable’ is nice as a catchphrase and aspiration, but it’s also important not to dogmatize that goal. Put another way, don’t let the perfect (100% renewable energy) by the enemy of the good (an increasingly, but not completely, decarbonized grid).

Source: Energiewende

An inspirational tidbit I took from the history of transformational times in the energy sector was that during the Industrial Revolution (and the advent of steam power), the average Englishman “would be in no doubt about the occurrence of a revolution across the Channel in France, but he would have been astonished to learn that he was living in the middle of what future generations would also term a revolution.” This passage elicits optimism that despite the sometimes slow adoption of clean energy, the politicization of climate change, and the undue influence of heavily polluting corporations, we are hopefully deeper in the clean energy revolution than it sometimes seems– hopefully, future generations will look to today and know that we’re living in the heart of that revolution.

Rating

Content- 5/5: No matter your area of focus in energy, this book touches upon it. Starting from the beginning of society harnessing the world of energy around them (from animals to coal to gas to oil to nuclear to renewables and everything in between), Rhodes gives a fair treatment to these histories. And key to those histories, Rhodes focuses on the stories, the interesting characters, and the untold nuggets you likely haven’t yet heard.

Readability- 4/5: Rhodes isn’t short on stories to tell, and this extensive book reflects that (I’d be curious to see what ended up on the cutting room floor). But, in contrast to a ‘data dump’ type treatment you might see in similarly long energy books like The Quest, this one weaves more of a readable and digestible narrative, artfully done. The only knock I have on the book’s readability is that at times Rhodes gets too into the weeds of specific technologies (e.g., the intricate different ways people tried to solve the steam engine, when a more broad overview would suffice), which takes away from the human stories.

Authority- 5/5: Because of the lessons throughout this book, I feel like Rhodes left it to his readers to make the connections and conclusions about the future of energy. Rhodes’ gift as a historian and storyteller are on display, and his thorough research and knowledge is self-evident.

FINAL RATING- 4.7/5: At nearly 500 pages, this book is not a quick read– but for those who are genuinely looking to learn the history of the energy industry as you’ve likely never heard before, Energy: A Human History by Richard Rhodes is not one to miss.

If you’re interested in following what else I’m reading, even outside of energy-related topics, feel free to follow me on Goodreads and see my page of energy-related book recommendations. Should this review compel you to pick up Energy: A Human History by Richard Rhodes, please consider buying on Amazon through the links on this page.