The Electric Scooter Fallacy: Just Because They’re Electric Doesn’t Mean They’re Green

In cities across America, a cool new trend (or an invasive craze, depending on who you ask) is sweeping the sidewalks in the form of dockless electric scooters. In cities like San Diego, Austin, and Washington DC, electric scooters have been placed in every neighborhood by several companies that allow anyone to use an app to pay to unlock and rent the scooters. These electric scooters aren’t the rascal scooters you’re used to seeing in grocery stores and amusement parks across America, rather picture the Razor scooters ridden by children around the cul-de-sac that have been beefed up with an electric motor to enable travel at over 15 miles per hour, and then imagine dozens and dozens of them across a major metropolitan area. That’s the situation in these select U.S. cities, and the result is both an unexpected new means to get to the office, and also a bit of a public nuisance.

Source: Washington Post

While the issues brought about by these sudden ubiquitous personal vehicles are plenty (hazards to pedestrians, inappropriate parking that blocks egress, and the petty complaint that adults riding scooters simply look silly and unhip), the companies deploying the electric scooters are quick to point out their benefits. According to the tech startups behind the scooters, they are revolutionizing transportation. Such bold claims are nothing new from Silicon Valley companies who see their product as the next big thing, but the one claim that raised my eyebrow was that these scooters are taking cars off the road, reducing traffic congestion, and reducing overall carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. While the local press in DC has had a field day covering the whimsical, clumsy, and viral vehicles, I have not seen any investigation into these green claims. Transportation accounts for more CO2 emissions than any other sector in the United States, so any attempt to fight climate change must address transportation issues, but my intuition told me the claims that the electric scooters I’m constantly stepping over on the DC sidewalks reduce transportation-related emissions are dubious at best. How can a technology that requires electricity be better than manual alternatives like walking or biking? So much like I did when I grumbled about the lights always being left on overnight in the DC Tesla Store, I decided to run the numbers.

Note: I’ve since put out an updated version of this analysis that takes into account a scooter’s full lifetime from manufacture to disposal. Read that additional analysis here.

How dockless electric scooters work

The entire concept of personal vehicle renting through an app might be foreign to anyone living outside of a major city, but this type of transportation solution was borne out of the Uber/Lyft market that erupted years ago. Eventually, such vehicle sharing evolved to traditional docked bike-sharing. In bike-sharing systems, like Capital Bikeshare in DC or Citi Bike in New York City, customers go to one of the dozens of bike racks (or docks) across the city that has bikes locked and ready to be rented by the hour for a small fee or with an annual subscription. Riders can take a bike at one dock, ride wherever they want, and then return it to any bike dock in the city. While this concept revolutionized personal transport by allowing people who don’t own bikes to get around the city in a new way, this concept eventually evolved into dockless bike-sharing and then, ultimately, to dockless scooter-sharing programs. What these dockless scooter programs offered was the ability for riders to check the app (or an aggregator app) for the location of an idle scooter, unlock it with the app, and then drop it off wherever your trip happens to end without having to find a nearby dock. For this service, you’ll be charged on a per-minute basis. LimeBike, for instance, charges a $1 base fee for renting a scooter plus $0.15 per minute the scooter is in your possession.

Source: WAMU

At the end of each day, the scooters are collected to be charged overnight and redistributed where they’ll be needed the following morning. Take LimeBike, one of the several dockless scooter companies in DC, as an example. They distributed 50 of their electric scooters across the city earlier this Spring. Each morning, you can look at the LimeBike app and see those scooters evenly distributed across the city where people might use them to get to work. Once the battery on a scooter is low (which happens daily), it will lock and won’t unlock until it has been collected, charged, and redistributed. The scooters can be collected and charged either by an employee of the scooter company in an official company van or by third-party independent contractors the company pays on a per-scooter basis to collect and recharge the scooters at their homes overnight.

Collectively, these dockless scooters have logged hundreds of thousands (maybe even millions) of rides across the country in fairly short order. The appeal to riders is that they can get where they’re going up to fives times faster than walking, and unlike bikes they can allow you to arrive at work without fear of sweating from the exertion. Their electric nature also allows for easier climbing of hills, especially for people who might not be in physical shape for such a trip on a bike. Worth noting, too, is that several of these dockless companies also offer e-bikes that are powered by electric motors, but the rest of this article will instead focus on the unique characteristics of the electric scooter explosion.

Green claims

The companies behind the dockless scooters boast various advantages to the new mode of transport, including a quick and available solution to public transit’s first-mile/last-mile problem, accessibility for those unable to physically ride a bike or walk a significant distance, and even recapturing the child-like joy of riding a fast toy. The crux of my analysis, though, is the set of claims from the scooter companies about how their dockless electric scooters are helping to ‘green’ the transportation sector, taking cars off the road and eliminating CO2 emissions.

Source: Vox

One of the major dockless scooter companies, Bird, says the following:

Today, 40 percent of car trips are less than two miles long. Our goal is to replace as many of those trips as possible so we can get cars off the road and curb traffic and greenhouse gas emissions

Another major player in the DC electric scooter market, LimeBike, makes the following claim:

With the launch of Lime-S, we are expanding the range of affordable, space-efficient, and environmentally friendly mobility options available to D.C. residents of all eight wards.

These companies make claims of being environmentally friendly and reducing emissions, but no figures are provided to back them up. While each company is making “idealistic claims about solving urban congestion and reducing reliance on automobiles,” I find myself skeptical of how those claims would play out once the numbers are added up. So rather than sit here and grumble about potential greenwashing, let’s again bust out the back of the envelope to see if these companies are indeed greening up the DC transportation sector.

Calculations

The number of companies who are in this dockless scooter and bike market is growing, prominent companies in DC and other cities including LimeBike, Bird, Waybots, Spin, Ofo, Mobike, and Jump. Trying to use as realistic numbers as possible, I reached out to each of these companies to get specifications on the power use of the electric scooters and data on their ridership, but was met with either silence, a generic press release, or a reply that the answers to my question were proprietary. So, as these analyses often require, it was time to get creative.

Scooter specs

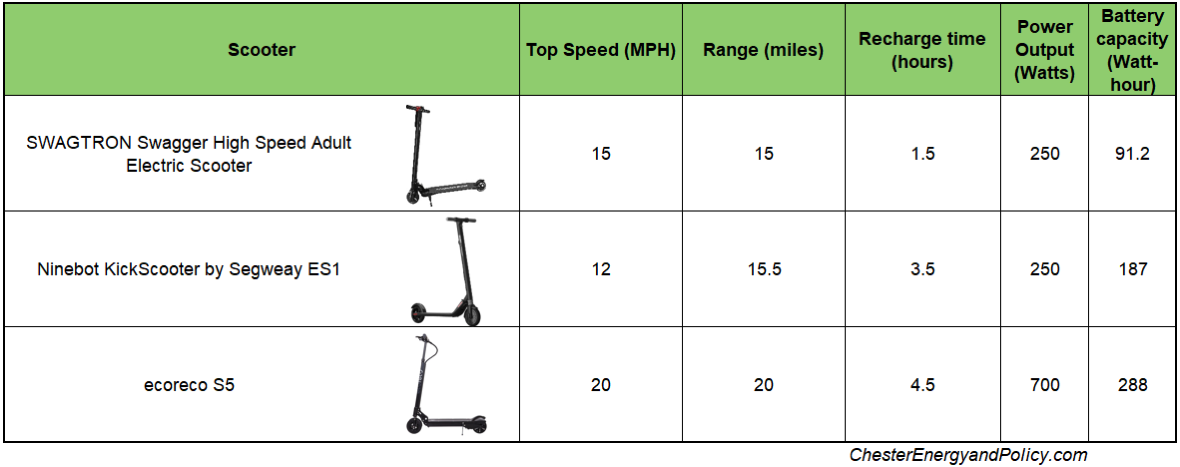

The specifications of electric scooters can vary significantly based on the model used. To get an idea, I looked at the scooters listed in this buyer’s guide of the best electric scooters of 2017. Narrowing down to the scooters similar to the ones on DC streets that also had power data readily available, the following three models appeared to be representative of the market:

Carbon dioxide emissions

To convert these figures to CO2 emissions associated with charging the scooters, on a per-mile basis, we just need to do the following:

Divide the battery capacity by the range, resulting in energy use per mile, and

Multiply the result by the emissions per watt-hour of the DC electric grid (~0.622 grams of CO2 per watt-hour).

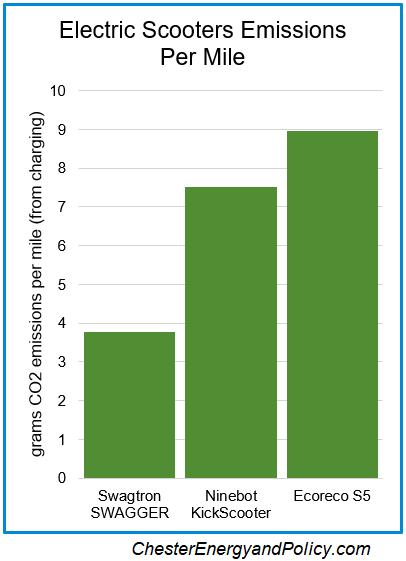

The resulting emissions per mile traveled for these three electric scooters appears as the following:

Comparing these figures, from about 4 to 9 grams of CO2 per mile, with the average emissions of an automobile on the U.S. roads today shows how much less emissive electric scooters are than cars on a per-mile basis:

So based on these numbers, riding an electric scooter accounts for only 1% to 2% of the CO2 emissions that driving a car the same distance does. This conclusion makes perfect sense, since an electric scooter is only moving the your body weight and its weight of about 20 to 25 pound, while a car typically weighs about 3,000 pounds. Moving that increased mass should require much more energy and thus increased CO2 emissions. So if the question is whether you should drive your own car on a several-mile trip or ride your own electric scooter, from an energy efficiency and CO2 emissions perspective, the environmentally-friendly decision is undoubtedly to ride the scooter.

But is it really green?

However, that conclusion does not fully answer the question regarding the dockless electric scooters, because of the following considerations:

Dockless scooters need to be collected and transported (usually by car or van) to where they can be recharged overnight before being transported again by car or van to their starting location the next morning.

Not only that, but the individual customer decision is rarely just between driving a car and riding an electric scooter. In cities with these dockless scooter programs, travelers will almost always have the additional options to ride a bike, hop on public transportation, or even walk– all of which would be more environmentally friendly.

One reporter narrowed down the usefulness of these electric scooter trips, noting their advantages are really restricted to trips “too long to just walk, that don’t offer a reasonable bus or Metro route, that don’t start or end downtown (How many of your daily trips match all three of those? For many of us, not a lot).”

Source: Recode

So the question to ask is how often are the trips that are being taken on scooters really trips that would otherwise have used a more CO2-intensive mode of transportation, as opposed to the many trips where scooters are being taken for their convenience or for the fun of using a scooter, as well as how carbon-intensive are the electric scooters if you factor in the need to transport them to be recharged at night? These questions are impossible to answer beyond educated estimates due to lack of data on individual consumer choices or recharging pickup data, but we can do our best to try:

Bird’s data suggests that, in San Francisco at least, each of its electric scooters gets used an average of fives times per day with each ride averaging 1.5 miles.

Bird caps the number of scooters a single contractor can charge per night at 20, but stiff competition among these contractors could limit them to 5 or fewer scooters to charge each night. So we can model the scooters being collected and distributed via car in groups of 5, 10, and 20.

No data is available for how far these contractors typically have to drive to collect and then redistribute these scooters. Based on the urban nature of the dockless scooter programs, we can analyze round trip routes that are short (2 total miles), medium (5 total miles), and long (10 total miles) as rough estimates.

The most efficient trips to collect and redistribute the electric scooters (collecting 20 scooters at a time and only needing a 2 mile round trip in a car to do so) adds 40 grams of CO2 emissions to each scooter’s accountability every day, while the least efficient trips (collecting 5 scooters using a 10 mile round trip) adds 808 grams of CO2 emissions to each scooter each day. In the middle, at 10 scooters and a 5 mile round trip, is 202 grams of CO2 per scooter every day.

So how do relative volumes of CO2 emissions change if the daily CO2 emissions from each dockless electric scooter (assuming the use of the most climate-friendly electric scooter analyzed above, accounting for the emissions from charging the scooters as well as driving them to be recharged) were replaced with cars, where each scooter’s 5 daily trips of 1.5 miles each needs to be traveled by an average U.S. car?

So dockless electric scooters still appear to be more climate-friendly than a car, even accounting for driving the scooters to and from getting charged. In our most-efficient case of recharging trips, the scooter accounts for 2% of the emissions of the car, whereas the medium-efficient case accounts for 8% of the car emissions and the least-efficient case accounts for 28% of the car emissions. However, it would still be incomplete to declare that the dockless electric scooters are eliminating CO2 emission from the transportation sector.

How can that be– aren’t I just being stubborn at this point? Perhaps, but it goes back to the idea that this calculation assumes a one-for-one replacement of car trips with scooter trips. As questioned earlier, how often is this actually the case? Scooters could be, and likely are, replacing options that are less carbon-intensive (biking, walking, public transit) just as often as they are replacing the more carbon-intensive act of driving.

In the most-efficient case, where each scooter accounts for 69 grams of CO2 per day compared with 3,030 grams of CO2 if the scooter’s 7.5 miles per day were replaced by car, as long as 1 scooter trip among every 44 trips are actually being used as an alternative to taking a car (say, hopping on an electric scooter instead of taking an Uber to get downtown), then the scooters are making a positive environmental impact. This proportion of trips actually displacing cars seems feasible. However in the least-efficient case, each scooter accounts for 836 grams of CO2 per day, meaning that if less than 27% of the scooter trips are actually replacing car trips then the scooters are actually generating more CO2 emissions than the cars would otherwise. Anecdotally from walking around downtown DC, I’m hard-pressed to believe that more than one in four of the scooter-riders I pass would otherwise be taking a car wherever they’re going (none of this is even to mention how pooling multiple scooter riders into a single car or Uber would tip the scales even further).

Conclusion

In the end, the exact degree to which these dockless electric scooter programs are actually ‘green’ is impossible to determine without data that is somewhat impossible to gather. They are, however, a fun new way to get around and they certainly do improve aspects of urban transportation, such as access to vehicles for those who are unable to use bicycles and options for the ‘first and last mile’ legs of trips. The opponents of these programs are also quick to point out their ills, such as what they mean for pedestrian safety, functional issues that make the scooters loud and dangerous, and their tendency to be parked in prohibited locations like in front of entrances for the disabled or even in the Potomac River.

Source: Washington Post

Passions for and against these scooter programs run high. Summarizing the two sides fairly succinctly, this article notes that “Supporters sing the virtues of cheap and accessible transportation with the promise of reduced traffic and cleaner air. Critics say the service gives rich tech employees a whimsical way to bar-hop at the expense of crowded and dangerous sidewalks.” However, trying to make the claim that they are aiding our cities’ green revolutions without evidence or event specific claims we can verify is misleading and incomplete. WIthout further evidence that these dockless scooter programs are actually moving the needle on CO2 emissions (evidence I would gleefully welcome from these companies and update my analysis with), they seem like a classic solution in search of a problem. While a common mantra of the clean energy transition is to ‘electrify everything’ (which lays the groundwork for decarbonization), this strategy of putting electric scooters all over the city streets is putting the cart before the carbon-emitting horse.

How can dockless electric scooters be utilized to actually clean up the city’s transportation sector in a way that effectively fights climate change? For one, these calculations would of course be different if the dockless scooters were outfitted with a solar panel that could recharge it over the course of the day. Absent that technology, the process would also make a definitive change if centralized renewable power was used to recharge the scooters and to charge the vehicles that gather the scooters each night (the companies could even start by purchasing renewable energy credits to offset their power use in order to make them effectively a carbon-neutral enterprise). Should one of the many dockless scooter companies in DC roll out such a system, I’ll be the first in line to praise them for actually helping to green up the transportation sector in the city. Further, if the dockless electric scooter companies make progress in the investment of infrastructure for green transport, such as Bird’s proposal that all dockless scooter companies pitch in a portion of their proceeds to help build bike lanes in cities and further green transportation options, then that would also have a downstream positive impact on the emissions of the transportation sector that would tip the scales in the long run. Until such changes are made, though, uncertainty reigns supreme and it is impossible to conclude that these dockless electric scooter companies are accomplishing anything other than greenwashing.

If you enjoyed this post and you would like to get the newest posts from the Chester Energy and Policy blog delivered straight to your inbox, please consider subscribing today.

To see other posts taking deep dives into energy data and CO2 emissions, see this post analyzing the costs of leisure driving through the years, this post on the CO2 emissions saved by the DC metro staying open later, and this post on the energy-savings case for the Tesla store leaving its lights on at night.

Sources and additional reading

Are electric scooters about to take over your city? The Week

Bird scooters roll out in D.C. and its executive wants to ‘Save Our Sidewalks’: The Washington Post

Electric Scooters Are Giving U.S. Cities Uber Deja Vu: Bloomberg

Scooter Startups Have Launched a Revolution. Can They Control It? Bloomberg

Scooters and Bikes Compete for City Streets: Bloomberg

The new gig economy? Charging electric scooters: Curbed

Welcome to Scootopia: we now aggregate all electric scooters: Medium